Eva Jones was erect, medium hued, with crisp, white hair and

challenging eyes. Her citation mentioned her involvements in social work,

teaching and archive preservation but my fascination was piqued by the person

rather than her recognised contributions. I was curious about her bright

confidence at an age when many of her contemporaries had long since adopted

infirmities and complacence.

Her proud carriage suggested military training and an

undaunted spirit shone in her smile as she accepted her accolade. As one whose

admiration the strength of Jamaican women had brought me to the island, I

recognised that she typified their independence and their overcoming. I

introduced myself to her and requested future contact. She nodded her head in

the direction of the road junction we faced and said, “I live there, at 2 Murry

Street.”

My first visits were tentative. My preparatory school was

demanding but I grasped occasional, fleeting moments of her company. She was

very reserved. Eventually she impulsively invited me to sit on her porch. Once there,

we found many common interests in her library for our reading seemed to follow

similar paths. Eva was far ahead of me on the journey, formerly a Rosicrucian

student, she had developed as a theosophist and had a firm belief in

reincarnation. She taught me about Lemuria and Atlantis and dwelt on the unity

of all faiths as explored in Isis

Unveiled by Helen Blavatsky. Her interest in promoting my thought was like

the Amerindian guide’s in Mary Summer Rain’s series which she recommended to

me.

My goal was to preserve her wisdom for myself and for future

generations. To facilitate this I tried to persuade Eva to allow me to write

her biography. She was extremely modest and careful of confidentiality. She

kept saying, “No, too many of those involved may recognise the parts they played

and I don’t want to embarrass anyone.”

Nevertheless, she let me write sample pieces of personal

recollections. She demanded historical accuracy so she suggested, “We go out

one Sunday morning, before any cars are around. We’ll walk the length of Great

George Street and I’ll show you how Savanna-la-mar used to be.”

This was the turning point of our endeavours. I was a member

of a group set up to explore sustainable tourism. It operated from parish to

parish, and had just spread to Westmoreland. The organisation was called SCF at

that time and executive members went to potential venues to find hosts and guides

who could promote their locality in a saleable way. As we walked, savouring the

town setting of Eva’s youth, I explained to her the prospect of community

tourism.

The next time I submitted a childhood story for Eva’s

conscientious scrutiny, she looked up sharply and said, “Alright, tell my

story, but you must fictionalise it and scramble it through history.”

An intense year of writing and research followed. Eva joined

the community tourism organisation on many of its trips and we theorised about

history and myth as lived experiences in the hills, valleys and plains of

Westmoreland. When she did not come herself, I reported trips back to her and used

the settings for stories in which heroines ranged from Taino days to the

current times in Jamaica’s history. There was no apparent link between each

part of the narrative except the indomitable spirit I had found in Eva Jones.

At the end of the year I left Jamaica for a four month stint in England during

which I needed to finish the book and find a publisher.

However, in real life events disrupts intentions. My line of

inquiry for publication proved mis-thrown. My time to write was invaded by the

need to earn. My plan to return home was delayed by unexpected political

decisions and family break down. Hues of

Blackness lay unattended to.

Yet adversity brings out the fighting spirit. I was summoned

to appear in court to defend my right to the marital home and my daughters’

recognition as joint tenants in fee simple. The tempestuous setting of Jamaica

did the rest. Rescued from a waterlogged former school room by my friend Eva

and marooned at her home whilst return flights were suspended due to a

hurricane, I wrote the narrative that turned our historical episodes into a

novel. I worked at night while Eva slept and we shared and evaluated the

results each day. I flew home with a completed manuscript. Internet searches

resulted in a joint venture agreement with Strategic Books and I was able to

make another trip to see Eva before I signed a contract.

By now Eva was well over ninety. Her capacity to walk was

failing and more of the sorrows of life had taken their toll. She felt she was

nearing the end. She listened to what I had to say then she said, “Publish it,

all of it.”

“All of it?” I queried, surprised.

“Yes, all of it, including the

biographical bits,” Eva affirmed.

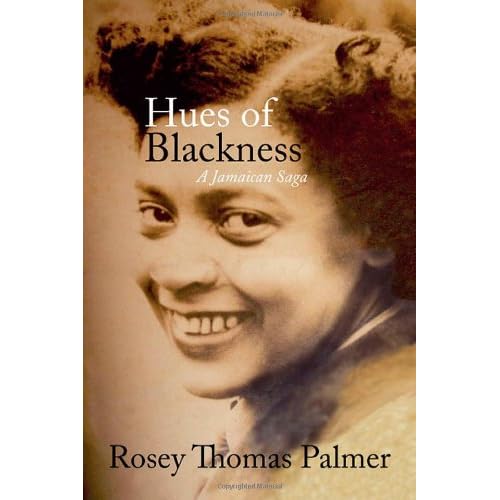

I was awed and relieved. During that trip she signed a

release letter for the anecdotal information she had shared and she gave me two

photographs. My book cover shows Eva, in the 1950s, provocatively locking the

gaze of the browser. I also have one of her in her eighties, looking proudly

down from the heights of her mango tree, which she climbed, machete in hand, to

tend a limb. If she is right and we are reincarnated, you may meet her one day.

If she was wrong you have not missed your chance of knowing this indomitable

woman. Between the pages of Hues of

Blackness: A Jamaican Saga you will meet her spirit.

Find out more on Rosey's Blog http://roseythomaspalmerauthor.wordpress.com