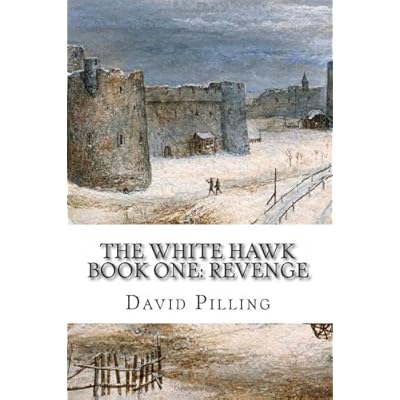

A Bolton, a Bolton ! The White Hawk!

"A Bolton, a Bolton !

The White Hawk! God for Lancaster and Saint George!"

England

The White Hawk follows the fortunes of a family of Lancastrian loyalists, the Boltons, as they attempt to survive and prosper in this world of brutal warfare and shifting alliances. Surrounded by enemies, their loyalties will be tested to the limit in a series of bloody battles and savage twists of fate.

The White Hawk follows the fortunes of a family of Lancastrian loyalists, the Boltons, as they attempt to survive and prosper in this world of brutal warfare and shifting alliances. Surrounded by enemies, their loyalties will be tested to the limit in a series of bloody battles and savage twists of fate.

This period, with its murderous

dynastic feuding between the rival Houses of York and Lancaster, is perhaps the

most fascinating of the entire medieval period in England

Apart from the savage doings of

aristocrats, the wars affected people on the lower rungs of society. One minor

gentry family in particular, the Pastons of Norfolk, suffered greatly in their

attempts to survive and thrive in the feral environment of the late 15th

century. They left an invaluable chronicle in their archive of family

correspondence, the famous Paston Letters.

The letters provide us with a

snapshot of the trials endured by middle-ranking families like the Pastons, and

of the measures they took to defend their property from greedy neighbours. One

such extract is a frantic plea from the matriarch of the clan, Margaret Paston,

begging her son John to return from London

"I greet you well, letting

you know that your brother and his fellowship stand in great jeopardy at

Caister... Daubney and Berney are dead and others badly hurt, and gunpowder and

arrows are lacking. The place is badly broken down by the guns of the other

party, so that unless they have hasty help, they are likely to lose both their lives

and the place, which will be the greatest rebuke to you that ever came to any

gentleman. For every man in this country marvels greatly that you suffer them

to be for so long in great jeopardy without help or other remedy..."

The Paston Letters, together with

my general fascination for the era, were the inspiration for The White Hawk.

Planned as a series of three novels, TWH will follow the fortunes of a

fictional Staffordshire family, the Boltons, from the beginning to the very end

of The Wars of the Roses. Unquenchably loyal to the House of Lancaster, their

loyalty will have dire consequences for them as law and order breaks down and

the kingdom slides into civil war. The ‘white hawk’ of the title is the sigil

of the Boltons, and will fly over many a blood-stained battlefield.

http://www.boltonandpilling.com/research

.JPG)